Asking which camera is best is like asking which car is best. You can't answer that question without knowing what the buyer's needs are. Do you need something small and portable? Weather resistant? Impeccable image quality? Versatile? Convenient? Each of these needs could send you in a different direction.

One major consideration is how far into the world of photography you want to get. If all you want is to take better photos of your kids' soccer/football games, then you can make your choice based on the features and price of an individual camera model. Test different models out in a store and choose whichever user interface you find most intuitive. If you think that you may eventually become a more serious photography hobbyist, then you need to need to consider the available upgrade path beyond your initial purchase.

Of course, it goes without saying (but I will anyway) that budget limitations will determine the style of camera you can acquire. Fortunately, a low end, consumer grade DSLR kit (a body, lens, and frequently a bag) can be had for just $500. Despite their price, the image quality and amount of user control offered by these models will run circles around any point & shoot camera. For $1000, you'll have a lot more choices that are a step above the entry level models. New, sub-$1000 models are release every couple months, so it would be pointless to recommend specific models here.

Choosing a system

If this purchase will signal the start of a new hobby, then you need to choose your system (camera brand and lens mount) first. The big advantage of DSLR systems is that the lenses, flashes, and other accessories are all interchangeable. You can upgrade and add individual pieces here and there without having to replace the entire kit... as long as you stay within the same camera system. If you decide to change systems -- such as jumping from Canon to Nikon -- you'll have to sell all your old gear and start over from scratch, because very little of it will be compatible. The more gear you already have, the more expensive this move will be. Life will be better if you choose the proper system from the outset.

When it comes to systems, Nikon and Canon are the big dogs. Nobody else can compete with their selection of lenses and accessories. If you can imagine a useful lens or accessory, it's probably available for Canon or Nikon. Virtually every pro uses one of those two. The second tier systems, like Olympus and Pentax, have a decent following that includes a few pros, but the selection of equipment (including compatible offerings from third party manufacturers) is more limited. Sony and Sigma are comparatively new to the DSLR world, so their long term expectations are still unknown. Once you get beyond the entry level kits, the big boys generally cost a bit more than the others.

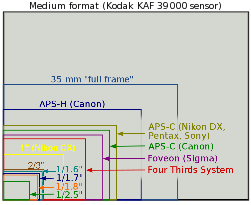

When it comes to systems, Nikon and Canon are the big dogs. Nobody else can compete with their selection of lenses and accessories. If you can imagine a useful lens or accessory, it's probably available for Canon or Nikon. Virtually every pro uses one of those two. The second tier systems, like Olympus and Pentax, have a decent following that includes a few pros, but the selection of equipment (including compatible offerings from third party manufacturers) is more limited. Sony and Sigma are comparatively new to the DSLR world, so their long term expectations are still unknown. Once you get beyond the entry level kits, the big boys generally cost a bit more than the others.Different systems have different characteristics. For instance, Canon typically makes higher resolution sensors than Nikon, but Nikons perform better in low light. Canon and Nikon offer both "full frame sensors" and "crop sensors." Full frame sensors are the same size as a frame of 35mm film (36x24mm). Crop sensors are smaller than that by varying amounts. "APS-C" sized sensors are roughly 22x15mm -- a 1.5x reduction. Pentax, Sony, and Sigma also makes APS-C sensors. Olympus uses a "four thirds" sensor, which is exactly half the size of a full frame sensor (17x13mm). By comparison, most point & shoot (P&S) camera sensors measure only about 7x5mm. Cell phone sensors are smaller still.

Many things are affected by the sensor size, and a full discussion is outside the scope of this article. One aspect has been detailed in a previous post. In short, larger sensors provide better image quality than smaller sensors, especially when the photo is taken in low light or when the image will be printed large. Smaller sensors magnify the reach of your telephoto lenses, which is helpful for sports and wildlife photography. Cameras with smaller sensors also cost a lot less.

|

| Canon 7D with Olympus 50mm f/1.8 lens |

Durability

If durability and weather resistance are high on your priority list, I've got bad news. While there are several sub-$400 P&S cameras that are impervious to the elements, you won't find that same level of protection for less than $2000. Some cameras in the $1000-1500 range are water resistant, but they can't handle being dropped in the ocean, and they can't handle being dropped from head height onto concrete. Underwater housings can be bought for most major bodies, but they cost many hundreds of dollars. I'm not aware of any DSLR that can handle the level of physical abuse that a purpose-built P&S camera can, although the magnesium frames in high-end DSLR's will certainly hold up better to abuse than will the plastic frames in the consumer lines.

Portability

If you're looking for something with better optics than a P&S, but that is still quite portable, you've got a huge and ever-growing range of options. Pro-grade DSLR's are the largest and heaviest you'll find. They're annoying to lug around, but the extra mass makes them very stable, and they fit better in your hand. Consumer-grade DSLR's are generally smaller and lighter, but they still won't really fit into most pockets.

|

| Olympus PEN E-P3 and 40-150mm lens |

Panasonic and Olympus created the MILC classification with their line of "micro 4/3" sensors, which are the same size as, but incompatible with, the Olympus DSLR 4/3 mount. Since then, several other manufacturers have jumped on the MILC bandwagon with great success, each with their own proprietary lens mount. This is easily the fastest growing segment of the photo industry. Of course, due to their recent introduction, there aren't a huge number of lenses or accessories available, but that's not why you buy a MILC. The major lens options are generally available, so you've still got your basics covered.

Lenses

So far, I've talked only about camera bodies, but let's not forget about all the lens options. In general, you have to make a tradeoff among image quality, convenience, and price.

Prime lenses -- those that have a fixed focal length and cannot zoom in & out -- typically contain the best optics and the best low-light capabilities at a relatively low price. They're also small and light weight. However, you'll frequently find your self swapping lenses or running about the room to capture the scene that you want. Not very convenient. For the record, 21 of the 29 lenses I own are primes.

Zoom lenses offer the ultimate in convenience, but at the price of either image quality or money. Pro-grade zooms perform reasonably well in low light, but cost $1000 or more. Consumer grade zooms are less expensive -- sometimes under $200 -- but sacrifice quality.

With zooms, you generally get the best image quality at the best price when your zoom range is limited. These lenses are "almost prime." Super-zoom lenses like the Tamron 18-270mm or Sigma's 50-500mm "bigma" cover an enormous range of focal lengths for the ultimate in convenience, but you may see distortions at the extremes of focal length and aperture.

Of course, sometimes, convenience is what you need. If you're walking around a foreign town all day on vacation, you want to minimize bulk. If you're out in windy, dusty, or wet conditions, changing lenses can let a lot of undesirable crud inside your camera body. And obviously, if you're on a tight budget, covering all your basis with a single lens is a bonus. In all of these situations, a super-zoom is a great way to go.

I could go on about this for hours, and I'd be happy to help you with specific examples if you can narrow down your criteria. Just speak up in the comments section below. Hopefully, the above will give you a good starting point from which you can help yourself or your shutterbug loved one make the jump to a nicer camera than they've currently got.

No comments:

Post a Comment

Please leave your comment below. Comments are moderated, so don't be alarmed if your note doesn't appear immediately. Also, please don't use my blog to advertise your own web site unless it's related to the discussion at hand.